Why the Pharmaceutical Companies are Failing

An earlier version of this article, with more extensive footnotes, can be viewed here.

THE STRENGTH OF AMERICA'S market-based economy lies in the way it devalues companies whose business models no longer deliver goods and services efficiently. Some examples:

- In 2005, GM lost $4.8 billion on its North American auto operations in the first nine months, during one of the best car markets in history. Its shares fell almost 54 percent. GM's market cap now stands at 1/15th that of Toyota's and is dropping.

- During the early 1990s, major hub-and-spoke commercial airline carriers lost every penny they had made since Kitty Hawk. All the legacy carriers either have filed for or are facing bankruptcy.

- Merck, one example of the pharma industry, saw its profits shrink in each of the last three years. Over the past five years, the company's stock price has fallen 70 percent.

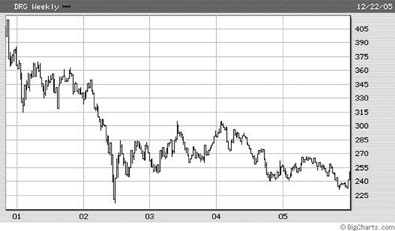

The graph above demonstrates the five-year weekly stock value of the US Pharmaceuticals Index. The pharmaceutical companies have been unable to move from a blockbuster1 to an orphan2 based business model.

The Ailing

Pharmaceutical Industry

Perhaps the most salient criticism of the industry comes from within. According to

Sidney Taurel, Eli Lilly's chief executive, "pharmaceutical manufacturers are

failing in their core competency. They do an awful job of finding new medicines. They

have been unable to get beyond reliance on billion-dollar blockbuster drugs that are

both over marketed and over prescribed."

Non-proprietary generic products are displacing the blockbuster, billion-dollar drugs. In fact, generics have now reached critical mass in the market. It's possible to treat a broad range of common conditions without any brand-name drugs. Some 60 percent of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, compared with less than half in 2000.3 Finding new blockbusters is a ubiquitous problem.

Poor lab productivity is bedeviling almost every drug manufacturer; across the industry, total FDA new drug approvals dropped 47 percent from 1998 to 2004. The reason is not difficult to decipher. Based upon information in public filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, U.S. drug companies spent almost 21/2 times as much on marketing, advertising, and administration as on research and development over the past half decade.

The drug industry spends far more on salespersons than on scientists. Its army of nearly 70,000 U.S. salespeople costs roughly $7 billion a year. They often deliver information doctors need, but at a high cost: The average sales call lasts seven minutes and costs companies $100 to $300 each.

Furthermore, most of the industry's research is not innovative. Publicly filed data demonstrate that most industry spending is for developing "copycat" or "me too" drugs. (Think Mevacor, Zocor, Pravachol, Lescol, and Lipitor.) These drugs do not provide a qualitatively different treatment than existing drugs. Their primary purpose is to evade competitors' patents and game the system. According to the Food and Drug Administration, more than 70 percent of drugs approved in the last decade fell into this category.

Extending the

Blockbuster

Companies in mature industries that have difficulty meeting the evolving demands of

the market attempt to extend their dominance through advertising, acquiring

competitors and exploiting political relationships. All have appeared in the quest to

extend the blockbuster market.

For the past decade, the pharmaceutical industry has gradually shifted the core of its business away from the unpredictable and increasingly expensive task of creating drugs and toward the steadier business of marketing them. Pharmaceutical manufacturers have become the biggest advertiser in the world since the Food and Drug Administration first allowed branded drug ads for consumers in 1997.

In 1998, Schering-Plough Corp. spent $136 million advertising just one medicine, its allergy drug Claritin, according to the research firm Competitive Media. That is more than Coca-Cola Co. spent advertising Coke, or Anheuser-Busch spent advertising Budweiser beer.

In 2003 alone, the industry spent $3.22 billion on direct consumer advertising.

Since 1994, there have been 38 major drug company mergers. These new combined companies generally lose market share and shareholder value, because of the disruption in the labs. The new company invariably has a product pipeline significantly smaller than those of the predecessor companies.

Finally, since 1998, drug companies have spent $758 million on lobbying the government - more than any other industry.4 The pharmaceutical industry has 1,274 lobbyists at the federal level, more than two for every member of Congress. Phar-maceutical executives and employees donated more than $17 million to candidates for federal office in 2004, favoring the governing Republicans 2 to 1.

The return on this investment? Drug companies won coverage for prescription drugs under Medicare in 2003. (The Bush Administration's price estimate has escalated from $400 billion over the next decade to $720 billion.) In addition, the law blocks government from leveraging its purchasing power to negotiate prices downward.

Drug companies have so far kept out imports of cheaper medicines from Canada and other countries. In addition, they have protected a Food and Drug Administration program that uses company fees to speed the drug-approval process for their products.

No other corporate investment brings returns even close to those of political bribery. There is a fine and sometimes indistinct line between actual bribery, which requires a specific quid pro quo, and legal mutually beneficial conduct. Contributing to political campaigns costs relatively little and generates huge returns. The government not only determines which products drug companies can market and how they are labeled, but also buys massive quantities of drugs through Medicaid, the Veterans Administration and other programs. With the new Medicare prescription drug benefit taking effect, the government will pay 41 percent of Americans' drug bills, up from 24 percent.

The Predictable

Future

Any failing sector of the economy, including the pharmaceutical industry, can inflict

tremendous damage as it collapses. Unless new approaches to developing and delivering

pharmaceutical products are in place - and soon - catastrophic consequences will

unfold for medicine and the economy.

The consumer of health care products and services is in open rebellion and the entire pricing structure for pharmaceutical products is about to collapse.

In a recent poll, the Kaiser Family Foundation,5 asked consumers why they thought health care costs were escalating. The most frequent response was excessive profiteering by drug companies. Consumers' interest in product cost coincides with their increasing exposure to pharmaceutical prices. Health insurance beneficiaries are paying larger amounts out of pocket for drugs through more sophisticated, multi-tiered prescription plans. This increase in financial liability is igniting a consumer rebellion, especially among aging baby boomers.

Specialty drugs will continue to cost more than patients can afford to pay.

Spending on specialty pharmaceuticals - biotechnology drugs and other expensive medicines prescribed by medical specialists - is growing twice as fast as traditional prescription drugs.6 Furthermore, this spending will grow by between 20 percent and 50 percent annually.7

In the last five years, the prices for specialty drugs rose 40 percent per year while overall drug costs rose 15 percent. These drugs have become a multibillion-dollar product line for pharmaceutical manufacturers. With no cap on prices and patients with few options, companies can profit in small markets - charging as much as $600,000 a year per patient for drugs needed for a lifetime.

Even after the seven-year monopoly for specialty product expires, there is often no competition for many "orphan drugs." That is because there is no federal process for approval of generic versions of biotech orphan drugs.8

New product development will be inhibited.

Pharmaceutical company investors do not countenance long-term bets on developing high-risk, breakthrough technology. They have generally off-loaded this risk to the taxpayer. The industry claims to spend about $27 billion a year on research but most of this is used to game the patent system. Significantly, greater funding each year comes from universities, charities and direct government support through the National Institutes of Health for basic science research that leads to breakthrough discoveries.

Most key pharmaceutical breakthroughs of recent decades have resulted from research supported by the government or the nonprofit sector, not drug companies. Examples include the polio vaccine, understanding the immune system, learning how to modulate inflammation, understanding the role of chemical balance in the central nervous system, defining the role of enzymes in lipid metabolism and understanding the virology causing AIDS. These discoveries have delivered the blockbuster patents to the drug companies.

Breakthrough research in cutting edge technologies such as nanotechnology9 and regenerative medicine are far beyond the investment capability of private pharmaceutical corporations.

The quality of academic research will deteriorate further.

The dependence of academic research on pharmaceutical funding tips the focus from basic research to applied studies that yield a more immediate return on investments.

Medical school faculty members are overly dependent on research funding from pharmaceutical companies. Last fall, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study of 108 medical schools showing that more than 90 percent let pharmaceutical companies exert significant inappropriate control over research in these institutions.10 These medical schools rarely ensure that their investigators have full participation in the design of trials. Research faculty members lack unimpeded access to trial data and do not have the independent right to publish their findings.

Thirteen of the world's leading medical journals joined in speaking out against the inherent risk of drug company funding for research and the resulting distortion of scientific research data for the sake of profits that result.11,12,13,14,15

Complaining about the problem is inadequate. In the future, scientific journals need to require an independent audit of the accuracy and completeness of research reports before they are sent out for peer review. These scientific auditors should be statisticians and medical experts who are completely free of conflicts of interest. The auditors must be given unfettered access to all of the data.16

Over the last 25 years, clinical research has been largely privatized. Three-quarters of the clinical studies published in the three most respected medical journals are now commercially funded.17,18,19

As a result, our medical knowledge grows not in the direction that best improves our health but toward corporate profits. The sad product of all this data spinning: most of the evidence in "evidence-based medicine" is more infomercial than dispassionate science.

This was not always so. Before 1980, most medical studies were publicly funded, and most academic researchers scorned industry support. Now the vast majority of clinical trials are commercially funded. With the financial stakes so high, there is mounting evidence of scientists and corporations manipulating their findings.

In addition, most senior medical faculty members who serve on boards that review patient safety in clinical trials in academic institutions are paid consultants for the pharmaceutical industry. As of 2001 and early 2002, 94 percent of medical faculty on institutional review boards had relied upon pharmaceutical manufacturer financial support for their research activities.

A Proposal for the

Future

Once upon a time, the patent-protected pharmaceutical manufacturer business model was

a relative success. Pharmaceuticals, many being enzyme inhibitors, have literally

transformed health care over the last several decades. Previously untreatable

illnesses are now prevented, cured, or managed effectively with drugs. The problem is

the industry's growing inability to meet medicine's future needs.

We are entering an historic flex point in health care. Medical therapy is leaving a one-size-fits-all model and entering individualized medicine. "Pharmaco-genomic" tests will detect the individual patient's susceptibility to disease and predict his or her response to therapeutic options. This genetic-based evaluation will dictate therapeutic design (and reduce adverse drug reactions that cause 100,000 deaths and two million hospital admissions each year in the United States).

The pharmaceutical manufacturing business model - based on blockbuster products that are based on patents that are based on intellectual property, mostly paid for by the taxpayer - is no longer working. What we need is a pharmacy business model more like that of the electronics industry, where innovation and competition drive down consumer costs. Electronic technology consumer pricing has plunged 88 percent since December 1997, while the consumer price index as a whole rose 22.5 percent.

The electronic industry's decline in price is attributable to improved manufacturing techniques and increasing levels of competition - both conspicuously lacking in the pharmaceutical industry. The technology sector has consistently produced more powerful but less expensive devices, ranging from cellular phones to microwave ovens and personal computers.

Just as the exponential growth in computing power has driven the favorable cost curve for technology, so too the growth in genomic derived therapeutic sites20 should stimulate competition and drive down pharmacy costs.

How do we construct a pharmaceutical industry that does that?

It will require restructuring in both private and regulatory sectors. We need a generic-based pharmaceutical industry with open sourced research that is not based upon proprietary, patent-based monopolies.

The federal government would increase its spending on pharmaceutical research enough to make up for the non-productive spending of the current system. This would increase costs by between $5 billion and $28 billion.

With the government now paying for more than 40 percent of all pharmaceutical costs starting, the additional public funding would be more than offset by lower drug costs in entitlement programs (such as Medicaid, Medicare, and VA) and pension plans for public employees. Savings in the private sector would be a bonus. Current estimates project the savings from this structural change would generate more than a 10 to 1 return, or about $200 billion a year, in drug spending.21

Researchers in universities, foundations, and the NIH who focus their efforts on basic research would be the primary recipients of new pharmaceutical research funding. Basic research leads to breakthrough biotech, nanotech and regenerative technologies, and is the appropriate area for future research investing.

In addition, funding non-private, non-patent-based research opens the way for better cross-pollination between the sciences. Just as in the past where new chemicals to treat disease were discovered serendipitously, in unexpected places such as the rain forest, answers to new medical technologies will come from fields such as engineering and physics, outside the biology discipline.

The only real difference from today would be that taxpayers, through government and not-for-profit grants and contracts, would fund the research. All findings would be available to the public. All manufacturers would have access to this data and be free to compete in the market. There would no longer be a need for direct to consumer advertising. The incentive to subvert governmental policymaking with political contributions would be gone. And the army of drug reps traipsing though doctor's offices hawking proprietary "me-too" products should disappear.

There is a model for a not-for-profit pharmaceutical company. As reported in the April 14, 2005 edition of the Economist, the Institute for OneWorld Health22 focuses on infectious diseases that ravage third world countries.23 OneWorld raises development funds from non-commercial sources and enlists researchers to contribute their expertise pro bono. With public funding, this model would have the resources to focus development on the needs of medicine, not the interests of corporate shareholders.

Any debate about alternatives to the current patent-based pharmaceutical industry will draw the attention of legions of experts. Many with ties to the industry will argue that medicine's future will collapse without the "vital" role played by the drug companies.

But we have little choice but to consider such alternatives as the generic-based option. We can no longer permit the declining pharmaceutical manufacturers to damage public policy making, destabilize entitlement programs, destroy retirement plans, degrade the research quality of our academic institutions or exact unconscionable profits from defenseless patients.

Over the horizon, medicine requires affordably priced orphan drugs, which the patent-based industry cannot deliver. The cost for these new technologies can only come from federal research funding.

It is time to thank the pharmaceutical companies for their past contributions and wish them success in their future - outside of medicine.